For well over a century, no one in her family lineage knew what led to the mysterious disappearance of a little girl named Emma from Garden River, an Anishinaabe community situated just east of Sault Ste. Marie.

Emma was seven years old in 1907 when she was uprooted from her grandparents’ home in Michipicoten by an Indian agent — along with her older sister, Fannie Nolan — and placed in St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School in Fort William, Ont. Three years later, she ended up in a Port Arthur hospital.

Emma was never seen or heard from again.

But Carol Hermiston, an Anishinaabe elder-in-residence at Algoma University and Nolan’s granddaughter, believes she has discovered the final resting place of her great aunt Emma more than 110 years later: in an unmarked grave inside a Catholic cemetery in Thunder Bay, Ont.

“Emma, as far as I know, is the only little girl from this area who didn’t make it back home,” Hermiston says. “She was sent to Thunder Bay when she was seven years old and she died up there when she was 10. There’s been nothing said, nothing has happened, nothing to acknowledge it.”

“It’s heartbreaking,” she continues. “It’s a very heartbreaking story.”

Since last year’s discovery of 215 potential unmarked burials at a former residential school site in Kamloops, B.C., many Canadians have had their eyes opened to the country’s darkest legacy: for more than a century, the federal government rounded up Indigenous children from their families and forced them to attend church-run schools, where assimilation, not education, was the primary goal. According to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, more than 3,200 students died at those institutions, with hundreds never properly identified.

Deeply disturbed by what she read about in Kamloops, Hermiston couldn’t help but think about her long-lost ancestor. During one of her regular walks along the shoreline of Batchawana Bay, she made the decision to seek out the truth, once and for all.

“Every day that I walked, I saw two eagles,” she says. “It just struck me: I have to find Emma. I’ve got to find Emma.”

Over the course of last summer, Hermiston would begin collecting records, obtained by herself and others, in an attempt to piece together Emma’s elusive story. It was old-fashioned detective work coupled with a bit of luck.

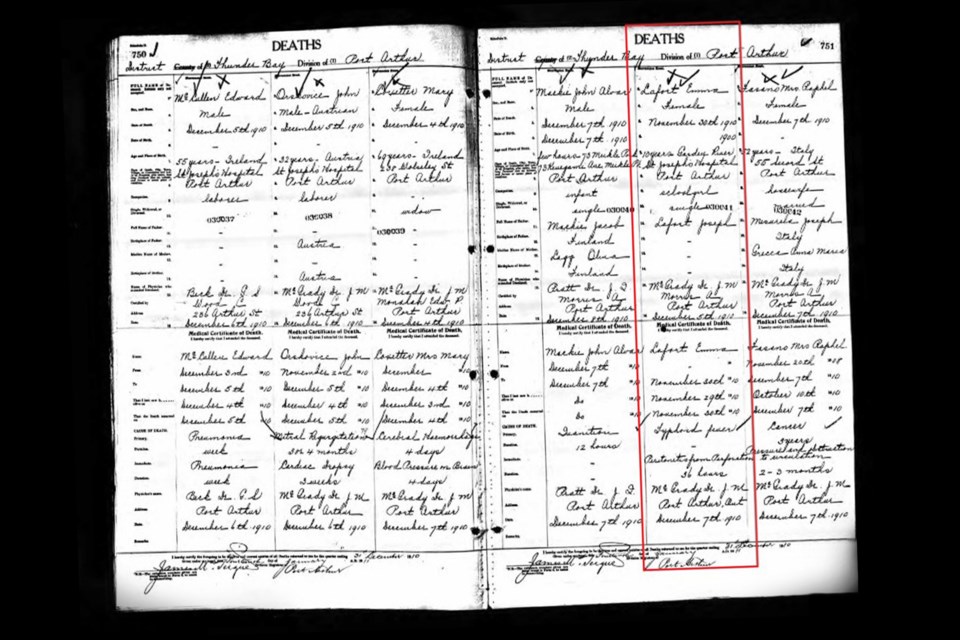

Her first call was to the Thunder Bay Catholic District School Board, but she came up empty-handed. She then connected with a cousin from Nova Scotia who had been conducting her own genealogical research. That cousin would eventually obtain Emma’s century-old death certificate, which she immediately shared with Hermiston.

The handwritten entry listed Emma’s date of death: November 30, 1910. She was just 10 years old.

Archived long ago, the certificate lists the cause of death as typhoid fever. It also notes that Emma suffered from peritonitis — an inflammation of the thin layer of tissue covering the inside of the abdomen — arising from ‘perforation,’ or what’s more commonly known as a rupture.

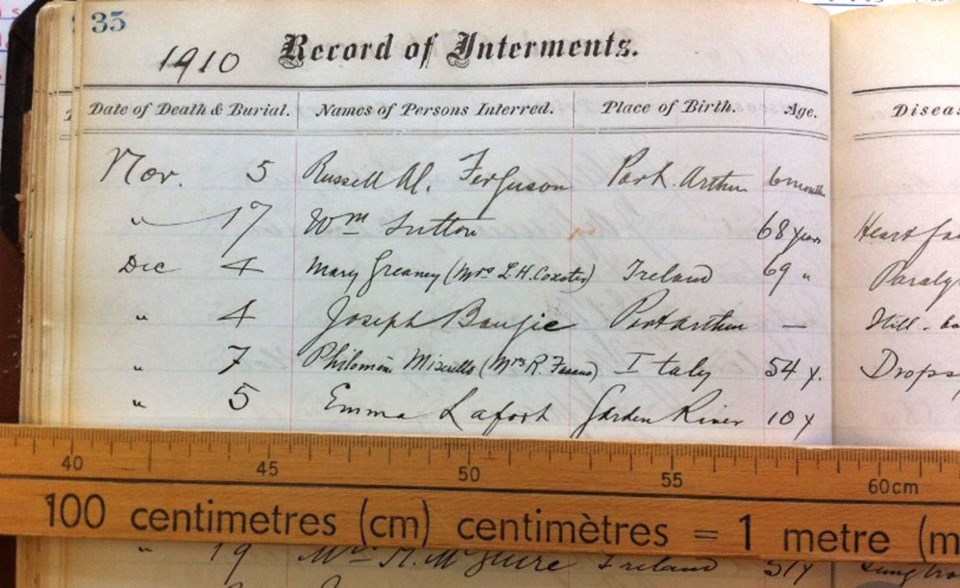

Hermiston continued her search, cold-calling funeral parlours in the Thunder Bay area with no success. Eventually, one funeral-home employee passed along another critical clue: during the period Emma died, only two cemeteries existed in Thunder Bay.

That nugget of information led Hermiston to a secretary at St. Andrew’s Catholic Cemetery. During their conversation, Hermiston not only discovered that Emma was interred somewhere in that cemetery — after her body had been stored in a vault over the winter due to the ground being frozen — but that the little girl was buried in what Hermiston describes as an unmarked “mass grave” containing the remains of other children.

It is not clear if any of the other children buried there were students at St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School, which was originally established in 1870 as the Orphan Asylum of Fort William and demolished in 1966.

During her conversation with the secretary, Hermiston also learned another surprising detail: two other individuals had visited the cemetery recently to inquire about Emma. Clearly, Hermiston wasn’t the only person trying to solve the mystery of her late relative.

In a twist of fate, their paths would soon converge.

It turned out the two visitors were Travis Boissoneau, a deputy grand council chief at the Anishinabek Nation, and his acquaintance David Thompson, who has been compiling residential school records for a number of years. By chance, Thompson had come across Emma’s name while sifting through records related to St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School.

Thompson had decided to reach out to Boissoneau, given his ancestral ties to Garden River First Nation. “I ended up meeting him at the cemetery,” Boissoneau says of Thompson. “He was sending all the information he could acquire throughout the years.”

In mid-June of last year, Boissoneau decided to pass along Emma’s name to someone else: his friend, Tanya Talaga, an acclaimed writer and storyteller with roots in Ontario’s Fort William First Nation. Talaga worked for The Toronto Star for more than 20 years before becoming president and chief executive officer of Makwa Creative, a production company versed in Indigenous storytelling. Her great-grandmother, Liz Gauthier, was a residential school survivor.

“He just thought: ‘Maybe this is something you want to look into,’ ” recalls Talaga, in an interview with Village Media. “And honestly, this is so bizarre: days later, I just got a random message from Carol [Hermiston] saying she also knew my work and read my stories, and she was reaching out to me because she wanted help finding their relative.”

Hermiston says she decided to contact Talaga on social media after a relative sent her a 2019 newspaper clipping about the unveiling of a memorial dedicated to St. Joseph’s. “She messaged me back very, very quickly and I told her I was trying to find my grandmother’s sister who had died up at that school,” Hermiston says. “She said she would help me, but at the moment she was helping the family of another little girl who had passed from Garden River.”

Talaga remembers the exchange well. “I said: ‘I’m working on finding another girl from St. Joseph’s who’s buried at St. Andrew’s. She’s from Garden River.’ ”

Talaga didn’t realize it right away, but Boissoneau and Hermiston were telling her about the same lost child.

Hermiston then told Talaga who she was looking for. “She said: ‘My aunt never came home from residential school, and she was a little girl and her name was Emma,’ ” Talaga recalls. “I sent her a note that said: ‘Oh my God, what is your phone number?’ Because by then, I knew that we were talking about the same person.”

As soon as she finished speaking to Hermiston, Talaga contacted Boissoneau. “I was out golfing and Tanya texted me saying: ‘You would not believe who I just got off the phone with,’ ” he says. “And then she told me. I asked her to call me.”

He would connect with Hermiston later that night, in a phone call he will never forget. “It was quite emotional, seeing the worlds collide,” Boissoneau says. “And then I shared [Thompson’s] information and they ended up talking even later that evening.”

From there, everything started to come together. After connecting with Thompson, Hermiston would eventually obtain more historic records and documents needed to piece together Emma’s long-lost story. Knowing what we now know about the horrors of Canada’s residential school system, the records are difficult to read—yet another reminder of the pain and suffering endured by so many Indigenous children forced to attend those institutions.

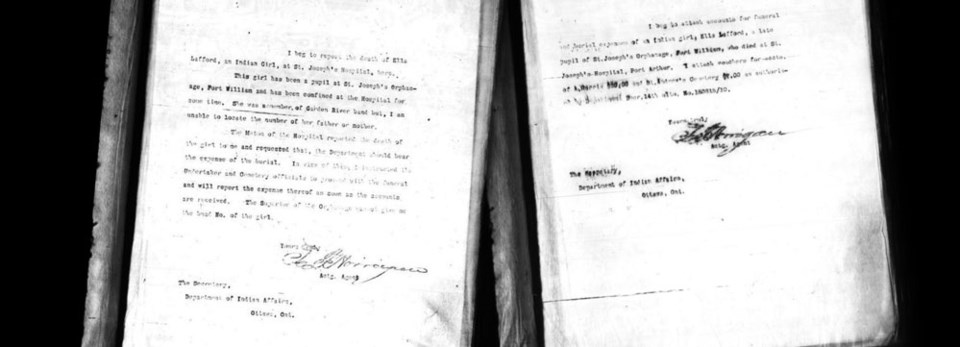

If nothing else, the documents show that both government and cemetery officials couldn’t even be bothered to get the girl’s name right. The child is alternatively referred to as ‘Ella Lafford,’ ‘Emma Laford’ and ‘Emma Lafort,’ leading to some confusion about the correct spelling of Emma's last name.

“I beg to report the death of Ella Lafford, an Indian Girl, at St. Joseph's Hospital here,” reads a letter from an Indian agent to the secretary at the Department of Indian Affairs in Ottawa. “The girl has been a pupil at St. Joseph’s Orphanage, Fort William and has been confined at the Hospital for some time. She was a member of Garden River band but, I am unable to locate the number of her father or mother.”

The letter continues: “The Matron of the Hospital reported the death of the girl to me and requested that the Department should bear the expense of the burial. In view of this, I instructed the Undertaker and Cemetery officials to proceed with the funeral and will report the expense thereof when the accounts are received.”

Another letter from the Indian agent indicates that the funeral and burial expenses were sent to Indian Affairs to be paid for. The letter also lists an $8 expenditure incurred at St. Andrew’s Cemetery.

Last August, Hermiston joined Thompson, Boissoneau and a couple of Hermiston’s family members in Thunder Bay to hold a ceremony for Emma at St. Andrew’s Catholic Cemetery. A month later, she held another ceremony at the Catholic cemetery in Garden River First Nation, where Emma’s sister, Fannie Nolan, is buried.

Hermiston had procured some earth from the Thundery Bay cemetery and placed it at Nolan’s gravesite. Symbolically, at least, the sisters were finally reunited.

Looking back, Hermiston is still amazed at the random chain of events that led her to Emma’s final resting place. “I don’t believe it just happened,” she says. “I actually believe that the spirit of my grandmother and Emma were leading me there.”

During the 1960s, Emma’s sister would often travel to Thunder Bay to pick up Hermiston’s sister, who attended school there. Each time Nolan went, she would spend time searching for the sister who never made it home. “She would go to the church there and the people who ran the school, but no one had any answers for her,” Hermiston says. “It was like Emma just disappeared.”

Boissoneau says that the story of Hermiston’s family is one of many, as Indigenous children being shipped off to residential schools far away from their homes was a regular occurrence. “I think the public needs to understand that our children were literally picked up, put on boats, put on planes and shipped far away from family,” he says. “It’s extremely tragic. I’m a father of three, and I look at my kids…I couldn’t take that, I couldn’t bear that.”

Hermiston says the search for Emma was a “moving and emotional journey” for her and her family. “For all intents and purposes,” she says, “Emma’s spirit has been brought back home.”

Talaga says the children who didn’t make it home from residential school are everywhere in Canada, and they all need to be brought back home. She also says that when you are Indigenous, there are no coincidences in life. She is convinced there was a deeper reason why she and Hermiston crossed paths.

“There’s some reason that she was guided towards me, and there’s some reason I happened to know about a little girl named Emma,” Talaga says. “Our ancestors speak to us all the time. You just have to make sure you listen.”

A national residential school crisis line has been established to provide support to former students and their families. The 24-hour line can be accessed at 1-866-925-4419.

James Hopkin is a veteran reporter at SooToday.com who previously worked as a journalist at CTV, APTN and CBC. Born and raised on Manitoulin Island, he is a proud member of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory.